One of the first things I learned about cooking in France is that white vinegar there is twice as strong as white vinegar in the US! I ruined several batches of Swedish dillsas for lamb, before discovering my error. It must be cut with water to use in an American recipe.

The second thing I discovered was that I had grown a “mere du vinaigre” in a plastic bottle of red wine vinegar! My best friend took it to her meme (grandmother) to have it trimmed and placed in a glass jar for me. Every year I feed it with the remnants of red wine or Banyuls wine, so I always have vinegar for my vinaigrette or to drizzle on oysters in the half shell. I‘ve never known any Americans who had a vinegar mother in their kitchen in the US, but I now have TWO in my French kitchen! This past year my daughter called to ask me what was wrong with her red wine vinegar as there seemed to be something weird at the bottom of the bottle. “Aha!,” I said, “You have a mere du vinaigre!”

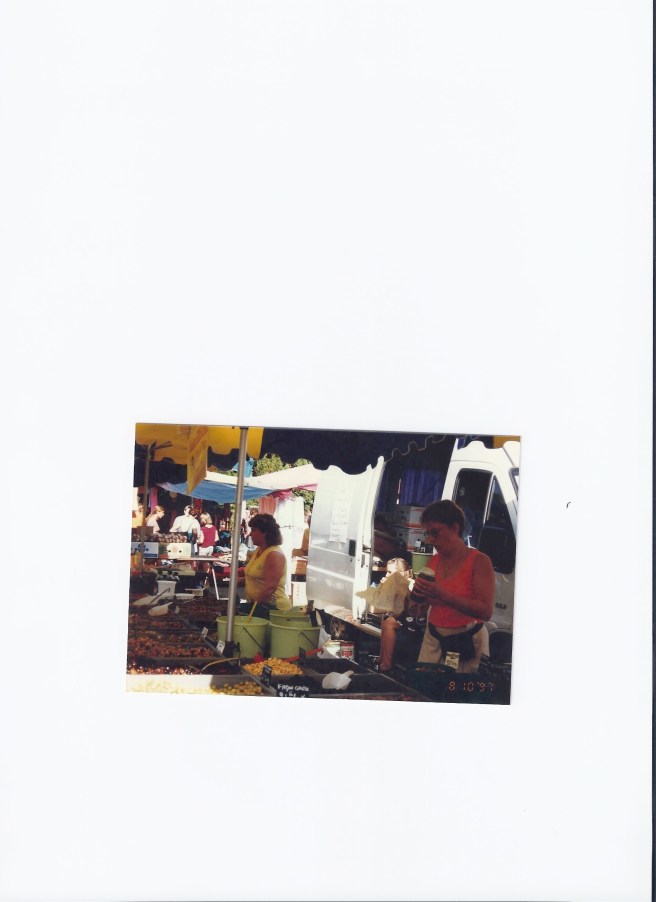

Our village has open markets two days a week, and we most often go on Sunday mornings as the church bells are ringing. It’s a lovely walk down the hill and a difficult walk back up again with groceries, so shopping bags on wheels are a necessity. We quickly found that the vendors stayed mostly the same every year, so we had our “olive ladies” and our “cheese man” and our “chicken man.” They seemed to look forward to seeing us every year and always asked about our daughter when she became old enough to be working every summer and unable to join us on a regular basis. Eventually the olive ladies left and were replaced by several other olive and nut stands, but they were never the same.

And the cheese man and his wife retired and were replaced by a lovely young lady who had bought their truck and business from them. She always has a big smile for us, along with a few new cheeses to sample.

Our chicken man originates from Portugal and makes the most marvelous Catalan chicken, which we look forward to every Sunday. I have not yet gotten him to give me his secret recipe, so I continue to experiment with vegetables and saffron and herbs, trying to get the sauce just right.

The merchants we see every year know us by now and every year we arrive with trepidation that our favorites may have retired or gone out of business. The grocery store on the main square has changed its name more times than I can remember, but we still refer to it as the Midiprix, a name from 30 years ago. One year we arrived to find that a hotel and a bar had been purchased by Swedish families. That year we had our Christmas glogg in their bar!

Fortunately we have a wonderful poissonnerie (fish shop) where I always find fresh catch right out of the Mediterranean, often provided by the fishermen at Port Vendres, the neighboring village. There we can always find fresh anchovies, fresh sardines and fresh mussels, among all the rest of the fresh fish on display. I enjoy trying to duplicate the mussel recipe of my chef friend in Cerbere: Moules Sang et d’Or.

A few years ago, my penpal from Australia visited us in France for a few weeks. She is a vegetarian but said she would eat fish. So for her first meal with us I planned a nice piece of cod on a bed of root vegetables (a Scandinavian recipe I’d picked up on a TV show). On the drive up from the Barcelona airport, I told her we were having cod. She groaned and said “Oh, that’s the one kind of fish I don’t like!” So I served her the vegetables and put her piece of cod on a side plate for her to taste. She ended up liking it so much that she plopped it onto her vegetables, just like we had on our plates, and ate every bite! She’d thought cod would taste like cod liver oil!

So I then took her to the poissonnerie and told her to pick out something she would like to taste. She chose filets of “rascasse,” probably because they were filets (no head or tail and off the bone) and looked nice with rosy skin. So I quickly sautéed the rascasse in olive oil for her and she loved it. She kept asking me what the name was in English and I kept stalling. The next day I sent her to the aquarium, which is in the University of Paris College of Marine Studies, located in our village, and there she found a rascasse swimming around in its tank.

She came back to the apartment, laughing and scolding me; she couldn’t believe that I’d not told her that the rascasse was a scorpion fish! It’s an experience she is still talking about. We use rascasse often in our recipes in France as it’s a nice mild white fish that lends itself well to several methods of cooking.

When taking American guests to restaurants in France, we remind them that an entrée is NOT the main dish, but IS an “appetizer,” as in the US, or a “starter,” as in England. I don’t know why that mistake was made when the word “entrée” came to the US, but it is very confusing to anyone traveling back and forth between the two countries. In France, an entrée is the first course (entrance to the meal), usually fish or a special salad or anything a bit smaller than the main course. I often serve fried sardines as an entrée or pate with toasts. Another time it might be salmon and potato pancake stacks with asparagus topped with hazlenuts.

A few years ago, I made stuffed artichokes and topped each with a fried squash blossom. It was lovely and delicious!

The courses are likely to go as follows: appetizers (such as nuts and olives) with drinks or a glass of Banyuls, then the following courses all with appropriate wines: mise en bouche (meant to be the chef’s sampling of a new recipe, this is usually a tiny glass of cold soup or a verrine, which is a layered appetizer, or a simply small crab cake, small tomato tart and garlic shrimp),

them the entrée, such as foie gras with onions and radishes (served to us at L’Auberge du Cellier in Montner),

then the main course, either meat or fish (such as red mullet on fennel),

then a variety of cheeses,

and then dessert, like crème catalane or kiwi meringue stacks,

then candy or cookies or small pots de crème and stuffed apricots with coffee,

then candy or cookies or small pots de crème and stuffed apricots with coffee,

and then sometimes a degustif (cognac, for instance).

Of course for really FORMAL dinners, the French will add sorbets and entremets and anything else they can dream up! As we get older, we find that we are cutting down on our courses, although my friends laugh at me and say they’ll never get a simple meal out of me. And I say the same about them. When my friend in Banyuls asks us to come for a simple supper, I am positive that she does not mean a bowl of soup and piece of bread!

Ah! Bread! Now there’s a whole chapter in itself! Whenever my French friend comes to the apartment for a meal I have to make a special effort to remember to put the basket of bread on the table. As an American, I find it very difficult to remember to serve bread with meals. Invariably we will begin our meal and then I will hear her ask me, “Do you have a little piece of bread, please?” It’s become an inside joke by now. With all the other preparations I am doing for all those courses, cutting the bread and putting it into a basket is just the last thing on my mind!

Last year I decided to learn how to make my own French bread as we can never find French bread in the US as good as what we buy in France. (Well, maybe in New York City we’ve had pretty good French bread, and once in the Cleveland area.)

It took a lot of flour last winter for all my tries, using Julia Child’s recipe, which takes 12 hours, by the way, and is over 20 pages long. I succeeded eventually in being able to produce a fairly decent batard and a boule, but will just wait until our return to France for the real deal.

In France I cook mostly fish or veal. The fish is fresh, right out of the sea, coming mostly from Port Vendres.

The veal in France is very tender and delicious. In the US, I am now in an area that gets very little fresh fish and when it does appear in the stores, it is filleted and has been in transit up to a week. Who knows how fresh it really is?

The veal that I find in my area of the US is either paper thin or in cubes. There’s no chance of stuffing a veal breast or roasting a shoulder of veal. On the other hand, I rarely buy beef in France, as it’s never as delicious as what we eat in the US. My daughter soon learned that French hamburgers always arrive from the Flunch Restaurant kitchen quite red inside. We do stop at McDonalds in the city, but only to use the restrooms! The McDonalds restaurants have automated kiosks in them for ordering and paying for your food, something that I see is now coming to the US. And of course they serve wine and beer in France.

I like my meat well-done, which I know is not de rigueur. I’ve given up ordering maigret de canard (duck breast) or almost any meat in a French restaurant, unless I know it is in a stew and well-cooked, because I know it will arrive on my plate red or pink, and indeed that is how it should be served! Even tuna should arrive red inside, but not for me. Sending a plate back to the kitchen to be further cooked often brings ire from the chef, so I try to avoid that scenario by just ordering something I don’t have to worry about.

And so I am just an ordinary cook, who has her own 4th of July on her balcony in France by eating fried chicken, onion rings, and cole slaw and reading the Declaration of Independence to the family, and then ten days later celebrates 14 Juillet with the rest of France, watching the local fireworks over the sea.